Originally posted on The Jewish Journal

By eighth grade, Micha Thau knew he was gay. But he also knew that being gay was not acceptable in many of the Orthodox spaces he inhabited. So he buried that part of himself.

But it didn’t stay buried. He began to suffer headaches, vertigo and other physical symptoms he attributes to his feelings of intense isolation. He relished days when the symptoms would send him to the doctor, just because “I got to leave the hellhole that was my life.”

“There were times when it was just crushing,” said Thau, 18, who graduates from Shalhevet High School next month. “I thought it was over, like I really could see no light at the end of the tunnel.”

Youth in Thau’s position face few options, none particularly rosy. They can quit Orthodoxy and live out gay lives, either as secular Jews or within another branch of Judaism. They can stay in Orthodoxy and renounce a part of themselves, living in celibacy or difficult relationships. Or they can do as Thau did and fight for openness and inclusion, and risk becoming poster children.

Still, as the secular world increasingly has embraced same-sex couples, the Orthodox has not been left totally behind. A number of congregations and communities, pulled by the conscience of some of their members, are taking a hard, wrenching look at their laws and traditions, and how they impact Orthodox youth.

When Thau came out during his sophomore year to Rabbi Ari Segal, Shalhevet’s head of school, and Principal Rabbi Noam Weissman, he was literally shaking. The administrators were surprised by the toll it had taken just to talk to them.

“We thought we had done an amazing job” promoting inclusion, Segal told the Journal. “And it turned out he had waited to come out to us because he was scared — he didn’t know what the school’s position was.”

Segal has since emerged as an advocate for teens like Thau. In an opinion column in the Shalhevet school newspaper, he called the dilemma they face “the biggest challenge to emunah [faith] of our time.”

Thau’s coming out has turned into something like a coming out for the entire Modern Orthodox community in Los Angeles: a highly visible test case for a virtually invisible issue. Thau has joined with Shalhevet’s administration to reshape perceptions of lesbians, gays and bisexuals in a religious community pulled in opposing directions — toward acceptance by its modernity and toward silence by its Orthodoxy.

The letter of the law

For the young people caught up in that struggle, the root of the problem lies in Leviticus, which labels gay sex a toevah, most often translated as an abomination, and, a couple of chapters later, prescribes the death penalty as punishment.

Strains of Judaism differ in how this law, like most laws, is applied. Reform Judaism suspends the prohibition, allowing clergy to officiate same-sex marriages. The two greater Los Angeles synagogues with outreach programs for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender members, Congregation Kol Ami in West Hollywood and Beth Chayim Chadashim in Mid-City Los Angeles, are aligned with the Union for Reform Judaism.

Conservative Judaism openly grapples with the law. As of a 2006 Rabbinical Assembly decision, gays and lesbians have been welcomed into Conservative congregations and rabbinical posts, but sex between men remains prohibited — the 2006 ruling did not address sex between women — and deliberations continue on same-sex marriage.

Orthodoxy generally adheres to the letter of the law, and homosexuality is no exception. Though outright hostility toward gays, lesbians and bisexuals is less common in the United States than it was before legalized same-sex marriage, so too is unconditional acceptance. Orthodox teens struggling with their sexual orientation in this environment can’t be sure how their communities will react if they come out, or whether they will risk losing friends and family.

It’s impossible to know how many teens are caught between their Jewish faith and their sexual orientation. Within the general population, multiple studies have found that around 3.5 percent of respondents self-identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual. But even those studies may not reflect an accurate count because not all respondents provide truthful answers, and many surveys, including the U.S. Census Bureau, do not ask about sexual orientation.

At Shalhevet alone, a school with an enrollment of slightly more than 200, general population estimates suggest there are something like eight lesbian, gay or bisexual students. Thau said he currently is the only out gay student at the school.

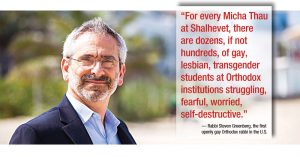

“For every Micha Thau at Shalhevet, there are dozens, if not hundreds, of gay, lesbian, transgender students at Orthodox institutions struggling, fearful, worried, self-destructive,” said Rabbi Steven Greenberg, the first openly gay Orthodox rabbi in the U.S. and an activist for LGBT Jews.

Walking a fine line

For Modern Orthodox communities, the word of biblical law translates practically into a stance that neither embraces same-sex partnerships nor outright condemns those who choose to undertake them.

“On the one hand, we’re not going to support it,” Rabbi Steven Weil, senior managing director of the Orthodox Union, one of the major national Orthodox institutions in the United States, told the Journal. “But on the other hand, we’re going to do everything we can to make sure that gay and lesbian members feel as much a part of the community as anyone else.”

Nonetheless, the model of an Orthodox marriage, without a doubt, is a husband and wife. Weil said, “Where there’s a little bit of pushback is where a couple wants to be discussed as ‘Mr. and Mr.’ or ‘Mrs. and Mrs.’ ”

For teens contemplating their romantic and religious futures, the range of answers they might receive from rabbis and school administrators is wide. For now, Shalhevet seems to represent the most progressive response they might receive in Los Angeles.

Valley Torah High School in Valley Village occupies a more conservative place on the spectrum. Reached by phone, Rabbi Avrohom Stulberger, the head of school, was quick to note that intolerance against gays, lesbians and bisexuals is not welcome.

“With my students, I feel it’s important that they understand that this is not something that we look down upon,” he said. “This is not a choice that people make.”

However, he wouldn’t budge on the issue of Jewish law: The rules are clear, and a student who wanted to live an out gay or lesbian life at the Orthodox high school would run into trouble.

“This would be inconsistent with the atmosphere — for a kid to say, ‘I’m gay, I’m acting out on it and I want to be a member of Valley Torah in good standing,’ ” he said. “It’s inconsistent from a halachic viewpoint.”

Asked whether such a student could, for instance, lead prayer services or school activities, he answered, “In 31 years, it hasn’t happened. But honestly, let’s just sort of change the question. I’d have the same dilemma if a kid came to me and said, ‘Rabbi, I love Valley Torah but I’m just eating at McDonald’s every night. That’s who I am.’ ”

At YULA Girls High School, the policy on gay, lesbian and bisexual students is in flux.

“We’ve had internal discussions, but we haven’t yet formulated a policy,” said Head of School Rabbi Abraham Lieberman, who plans to leave YULA Girls this summer after leading it since 2008. “It would obviously include the greatest amount of respect for the students and understanding of whatever they’re going through.”

He said the heads of the area’s Orthodox schools — including YULA Girls, YULA Boys, Valley Torah and Shalhevet — meet periodically to discuss important issues, including this one. As of now, they haven’t formulated a conclusion. But Lieberman expects that soon most local Orthodox schools will provide statements or policies on the matter.

As attitudes about homosexuality have shifted, with gay rights and narratives becoming more mainstream, hard-line positions have become more difficult to maintain.

Thau recalled telling his grandfather that he was gay and getting a surprising answer.

“He said, ‘So?’ ” Thau recalled. “And he said, ‘If you had told me that 10 years ago, I would have had a very different reaction.’ ”

Thau went on, “As much as the Orthodox community tries to isolate itself from the secular world, there are always cracks in the wall — no matter how high the wall is. Culture will always bleed through.”

Caught in the middle

But ensconced behind the walls of a Torah-observant lifestyle, many teens still face an awful choice between God and love.

“When you’re living in the Orthodox community, being gay and being religious — they’re not cohesive,” said Jeremy Borison, 25, who grew up in Cleveland and now lives in Los Angeles. “So me, if I had to choose one, I was gonna stay with the religious side of it.”

He said he’s now able to balance his faith and sexual orientation — but only because he found a welcoming community in B’nai David-Judea, an Orthodox synagogue in Pico-Robertson, where Senior Rabbi Yosef Kanefsky has been outspoken in favor of greater acceptance of gays and lesbians.

Others, like David, a gay man in his 20s who grew up in an Orthodox family in Los Angeles, no longer feel like they have a place in the Orthodox community.

Some of the gay and lesbian individuals interviewed for this story, including David, asked not to be identified by their real names or even the schools they attended, fearing they and their families would face sigma and untoward gossip. David still is wary about sharing his story publicly, for that reason.

At the Orthodox high school he attended in L.A., he knew he was attracted boys, but thought it was a phase, something all teenagers go through. There were no Orthodox Jews who were gay, as far as he knew; it simply wasn’t conceivable.

He had a good time during his high school years, though, enjoying his religious education and even getting close to some of the rabbis. But by the time he found himself in yeshiva in Israel, in a completely different environment, he realized his feelings weren’t going to go away. His first reaction was to treat them as something wrong with him that needed to be fixed.

A good deal of therapy later, David is leading an out gay life, but he finds that he’s uncomfortable in Orthodox spaces. His experience didn’t make him hate Judaism; he’s still finding his place in the religion. But he no longer considers himself Orthodox. How could he feel welcome in a community that considers who he is to be a great sin?

Every problem begs a solution

From time to time, students approach Stulberger, the head of school at Valley Torah, struggling with feelings of attraction to members of the same gender. Stulberger said he has “helped many students over the years in their struggle — but in a private way.”

His first reaction when students come to him with this issue is to assure them, “We are here to talk to; we are here to help you.” But after that he draws a line: “What I won’t do is give the indication that giving into your same-sex attraction is something that’s acceptable.”

To these students, he presents two options. One is celibacy. The other is to “get help, find the right professional who can help you to reorient.”

Stulberger alleges there are thousands of young men who have changed their sexual orientation with professional help. While the scientific and LGBT communities dispute its effectiveness, the internet is filled with testimonies from people who claim to lead happy, heterosexual lives as a result of “reparative therapy.” Stulberger even knows a handful of them, he said.

One of those is Naim, an Orthodox man in his early 30s who attended Valley Torah and who asked to be identified only by his middle name. For years, he struggled with his attraction to men but rejected the idea of living an out gay life.

“I didn’t want that lifestyle,” he said. “I wanted to get married. I wanted to have a family. I wanted to do what men do — period.”

By the time he was 28, he said, he’d been in and out of rehab for drug addiction and was addicted to gay porn. Then, he made an electrifying discovery on the internet.

“There’s a whole community out there — Jews and non-Jews alike — that don’t want to live that lifestyle and have struggled with it and gotten help, and now they’re married,” he said. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is incredible, God is talking to me right now. Why did it take 28 years to tell me this?’ ”

He enrolled in reparative therapy designed around what he called a “gender wholeness model.” He identified factors such as a troubled relationship with his father and an unhealthy identification with traits he admired in other men as the cause of his same-sex attraction, which he referred to as SSA. He treated it like a condition that needed to be fixed, he said, and he began to heal.

“My attraction for men has diminished significantly,” he said. “Usually, my SSA, on a scale of 1 to 10, is at a 0.”

Now, he’s looking for a wife.

“There are still days when I struggle every once in a while,” he said. “Thank God it doesn’t happen very often.”

Taking a pledge

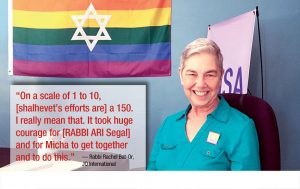

Told that a Los Angeles high school recommends reparative therapy, Rabbi Rachel Bat-Or of JQ International, a West Hollywood-based Jewish LGBT support and education organization, was horrified.

“What it does is, it encourages people to kill themselves,” she said. California law bans the practice for mental health providers.

David moved away from his Orthodox community after high school and hasn’t returned, but some of its stigmas and taboos lingered with him. He sought out reparative therapy while in college, and while he didn’t find it particularly traumatizing, he said it made him hate himself. Since then, he’s blocked much of it out in his mind.

Now, Segal and Thau at Shalhevet are asking other Jewish schools to affirm in a pledge, written jointly by Thau and the administration, that they “will not recommend, refer, or pressure students toward ‘reparative’ or ‘conversion therapy.’ ”

“We believe that’s damaging,” Segal said of the practice.

The pledge includes five other points — which Segal insisted schools can adopt altogether or individually — including an assurance that gay, lesbian and transgender students won’t be excluded from school activities and will be provided with support services. The full statement is available online at jewishschoolpledge.com. As of now, Shalhevet is the only school to have signed it.

Asked about the pledge, Lieberman, the head of YULA Girls, said, “It’s very powerful,” adding that if YULA Girls were to issue a policy about LGBT students, “it would definitely gravitate toward that.”

The idea of the pledge has its origins in Thau’s coming out to Segal and Weissman.

“What could we do?” Segal said he asked the teen. “What could we have communicated to you, Micha, that would have helped?”

The administrators realized that communicating anything at all would have been a good start. Even though both men assumed a gay student would be welcomed, Thau struggled through years of uncertainty because they had never said as much publicly.

“Schools and communities and shuls should have this conversation and decide what they believe, and then publish it,” Segal said — even if it is less progressive than what Shalhevet came up with.

Bat-Or said she hopes other schools will follow Shalhevet’s lead and take steps toward inclusiveness, for instance by circulating JQ’s helpline for LGBT Jews and advertising their counselor’s offices as safes spaces for students questioning their sexual orientation.

“On a scale of 1 to 10, this is a 150,” she said of Shalhevet’s efforts. “I really mean that. It took huge courage for [Segal] and for Micha to get together and to do this.”

A movement in the making

Cases like Micha’s make it increasingly difficult for Orthodox communities to ignore issues faced by their lesbian, gay and bisexual members.

“Centrist Orthodoxy is conflicted and not admitting the conflict,” said Greenberg, a Yeshiva University-ordained rabbi who came out years later and co-founded Eshel, a Boston-based organization that promotes inclusiveness in Orthodox communities. “They are pulled by much more traditional frames, and they are pulled by the human realities they’re facing.”

At least in some communities, that conflict has meant a long, slow drift toward acceptance.

Elissa Kaplan, a clinical psychologist who came out as lesbian 15 years ago while living in an Orthodox community in suburban New Jersey, has watched attitudes change before her eyes.

“The world has changed since then,” Kaplan, 55, said. “Gay marriage is legal now in the civil world. That’s enormous, and it has an impact. It matters. Even people who say they are not influenced in their attitudes by what happens in the secular world — it’s just not true.”

She’s felt the impact of those changes herself, she said.

“My wife and I would go into one of the kosher restaurants in the area and might get dirty looks from people,” she said. “That really doesn’t happen anymore.”

In Los Angeles, that change has played out in parlor meetings where community members get together to grapple with the issue of inclusiveness. In March, some two dozen Jewish teens and parents gathered in the dining room of a Beverlywood home, sitting on folding chairs and nibbling on cookies and cut fruit as they listened to Greenberg speak.

The parlor meeting was the work of Eshel L.A., a local group allied with the Boston-based organization. It first convened in June 2015, when Harry Nelson, a local health care attorney, invited community members to his home to meet Greenberg and Eshel’s other co-founder, Miryam Kabakov, the group’s executive director.

From there, they formed a steering committee. That December, they had the first of many parlor meetings on topics like how to curb homophobic comments at the Shabbat table and how to talk to their children about same-sex couples.

“The thing that struck me most with this issue is that the Orthodox tradition that I so value and the Orthodox lifestyle I so love were creating pain, intolerable pain, for people who are gay,” said Julie Gruenbaum Fax, one of Eshel L.A.’s principal organizers and a former Jewish Journal staff writer.

Fax and her peers are looking to create Orthodox spaces where lesbians, gays and bisexuals can exist openly and comfortably. Sometimes, that entails actually grappling with Jewish law. At the parlor meeting in March, Greenberg, 60, who has salt-and-pepper stubble and a professorial air, moved fluently through the halachah and commentary on the topic of homosexuality.

On the face of it, the law as it is appears in the Torah seems clear enough. Leviticus 18:22 states, “Do not lie with a male as one lies with a woman; it is an abhorrence.”

But Greenberg pointed out to his Beverlywood audience that the rabbinate has created work-arounds for all kinds of mandates and prohibitions, such as those against carrying objects outside the home on Shabbat or farming during a jubilee year. The laws governing these exceptions are complex, but the point is, they are negotiable — unlike homosexuality, for most Orthodox rabbis.

During his presentations, Greenberg is careful to allow room for dissent and questions, and community members frequently take him up. One woman at the meeting, who wore a long black skirt and said she’d adopted Orthodoxy later in life, admitted that the concept of full acceptance for gays and lesbians in the Orthodox community makes her uncomfortable.

“I did this to bring boundaries to my life, to my kids,” she said of her decision to begin strictly observing Jewish law. “So when we start to open things up, it scares me.”

She continued on the topic of boundaries: If you’re going to toss out the prohibition on gays and lesbians, she suggested, why not let women wear jeans instead of skirts?

Thau was sitting in the front row. As the woman went on, he turned around and began to cut her off, looking upset, but Greenberg gently put a hand on his shoulder, and Thau sat back in his chair. During an interview a week later, Thau said he was grateful to Greenberg for stopping him from saying something he might regret.

“I’m always in the hot seat as the poster boy for gay people, answering all the questions,” he said. “And it’s not a role I’m unwilling to take, but it is very difficult to be perfect all the time.”

Inching forward

Becoming a poster child is exactly what Nechama wants to avoid if she decides to come out.

A student at Shalhevet who asked that her real name not to be used, Nechama said she’s only questioning her sexual identity. But if she were to come out, she would be hesitant to speak about it with too many people at her school.

“I just feel very uncomfortable with the idea of being gay in a Modern Orthodox school,” she said.

While the school itself is progressive enough, some students come from more conservative backgrounds, she said.

She said she hopes to remain Orthodox, even though she struggles with some of the Jewish laws she’d be obligated to observe. To the community at large, her only plea was for empathy.

“We’re teenagers and we’re going through confusing times,” she said. She urged peers and parents “just to hear everything out, because it’s kind of hard to be alone in something like this.”

For his part, Greenberg is clear-eyed about the work in front of him: Creating a fully accepting Orthodox community will be neither quick nor easy. But he holds it as the responsibility of Orthodox leaders to sympathize with members of their communities who struggle with their identities.

“If you’re not willing to suffer with that kid who is caught in the crosshairs of this cultural and religious conflict,” he said, “if you’re not willing to be with that kid, then you don’t deserve the role of leadership.”

by Eitan Arom